The Election

The greatest presidential election upset in United States history happened when Harry S. Truman defeated Thomas E. Dewey in 1948. The vast majority of commentators, reporters, political analysts, and the like, in conjunction with the balance of the polls, predicted Dewey would soundly defeat Truman. Sure of the results, many newspapers were printed and distributed headlining Truman’s defeat well in advance of the final outcome. Everyone was surprised when Truman won. Many of us have seen the iconic image of Truman holding up a copy of the Chicago Daily Tribune announcing his defeat at his victory party.

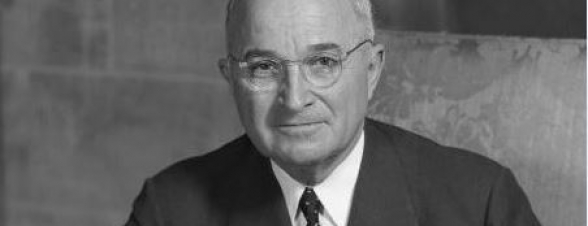

The son of a Missouri farmer, Truman entered Missouri politics before rising to become Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Vice President in 1944. Roosevelt was elected to his first term in 1932 in a landslide on his promise to bring the US out of the Great Depression. Roosevelt served as President through the Great Depression and the Second World War until his death in 1945, when Truman took office. As the Second World War came to a close under Truman, the union of various disparate political interests that had carried the Democratic Party during Roosevelt’s tenure as President began to unravel. This union, known as the “New Deal Coalition,” consisted of white southerners, labor unions, women, minorities, liberals, and the far left. It was widely predicted that the end of the Great Depression and the war would mean an end to this political union and a realignment of party loyalties spelling defeat for Truman. Well, it didn’t. Truman won.

Stock traders try to predict a company’s future earnings. Bond traders try to predict interest rate changes. Commodities traders try to predict future supply and demand. When Truman won, they were all caught off guard and reacted in one way or another. Financial markets experienced a correction falling more than 10% in the following months. Did everyone believe that a man who had already been President for three years was going to ruin the country in his second term? No. They were just surprised. The assumptions about the future upon which securities pricing models had been based were wrong and the markets regrouped and soon recovered.

In the long-run, the predictions of a political shift in our country turned out to be right. The “New Deal Coalition” did fall apart. The south did change parties; the north did migrate to the left. The American political landscape changed. More to the point, the US did not fall apart.

But what does 1948 have to do with today? A lot more than you might think.

Like 1948, we have seen shifts in American politics. In the primaries, Hillary R. Clinton, an establishment Democrat nearly lost to an avowed socialist, Bernie Sanders. In the Republican primary, Donald J. Trump, a New York populist, beat out a field of more qualified, traditional Republican candidates. These events mark a substantial departure from the party norms established decades ago. This deviation creates uncertainty. Again, markets abhor uncertainty. Until recently investors’ fear of the unknown was assuaged by the polls showing a fairly substantial lead on the part of one of the candidates. This alleviation felt by investors was not because the substantial lead belonged to Clinton, or because it belonged to a Democrat. It was because the outcome seemed clear and because Clinton is a party establishment candidate. But now the jitters are back as the gap closes between Trump and Clinton.

For some investors, the jitters are indeed a value judgement. However, for many investors it is the uncertainty that makes them anxious. Trump has largely abandoned the economic policies of Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush in favor of a brand of populism that has not gained traction in the US for some time. Whenever a nation embarks on a significant departure from old policies, for better or worse, volatility follows. Investors anticipate this volatility and dial back their risk, causing markets to decline. Just as in 1948.

As to the health of the economy going forward. The United States is a Republic. All power is not vested in the President. Our system of checks and balances thus far has, with one notable exception, prevented the election of a President from causing a precipitous collapse of our Republic (the notable exception being Honest Abe and the resulting Civil War). Regardless of one’s political leanings, we do not see a reason for investors to panic over the election.

Our long-term outlook? The American economy is strong and resilient, though there are ups and downs, the historical trend has been positive. We do foresee increased volatility moving forward, but if we hold tight we should be able to weather the storm.

Image from the United States National Archives and Records Administration.